I read or listen to around 4-6 books each month. This habit has helped me improve my business and grow on many personal and professional levels. But I’ve come to realize that as powerful as reading can be, I don’t get as much out of reading as I could. And that is because I am often a passive reader.

There is nothing inherently wrong with passive reading. It’s a great way to spend an evening or while away the hours on a road trip. It’s great for fiction, and for certain types of nonfiction in which you can be satisfied with consuming the book for entertainment value or for one or two big picture takeaways. Some well-written biographies or other non-fiction books can read like novels, providing entertainment, insight, and suspense. In those cases, active reading and note-taking aren’t required to benefit from these books—unless you are reading them for research purposes.

But I’ve read many powerful books focused on self-improvement, small business topics, and personal growth. These books resonate with me and inspire me to take action. But how well do I implement those steps? Do I create a plan of action and implement it? Or do I simply think to myself, “yeah, that’s a great idea—I should do that.”?

The answer is mixed. I’m good at grasping heuristics and assimilating top-level ideas into my ongoing mental models and thought processes. But I’m not always effective at implementing change on a deeper level.

I tend to forget more nuanced arguments authors make or I fail to implement multi-step processes. Over time, I find that what I’ve read drops off my radar if I can’t distill it into a five-ten second sound bite that I can quickly recall when needed.

Enter, Active Reading

I just picked up a copy of Effortless, by Greg McKeown. Effortless is the follow-up to his hugely popular book, Essentialism. Essentialism resonated with me on many levels and I have both read the book and listened to the audiobook.

However, several years have passed since my first reading of Essentialism, and I’m finding that there are some great takeaways that I’ve forgotten about. So I decided I would reread it before reading Effortless. This way I can have the Essentialist lessons fresh on my mind.

But instead of breezing through the book as I might have previously done, I am actively re-reading it while taking notes on passages, phrases, and examples that resonate with me.

By taking notes in a standardized format and keeping them in an accessible and centralized location, I will be able to revisit books I’ve read whenever I feel the need. This is something I wish I would have started ten years ago. But since I don’t have a time machine, the best I can do is to start now.

I also plan to write and publish a few select book reviews here on this site to keep a public record of my thoughts on the important non-fiction books I read. I’ll follow up with a review of Essentialism in the near future.

At this time, I don’t anticipate writing reviews of the fiction books I read or listen to. I consume fiction primarily for pleasure, and since fiction is highly subjective, I don’t have the desire to spend a lot of mental energy writing book reviews. There are dozens of other people who enjoy writing fiction reviews who will also do a significantly better job than I would. So I’ll leave it to them.

My Note-Taking Process

My note-taking process isn’t anything particularly complicated. I watched a couple of YouTube videos on how some people take notes, then realized it doesn’t matter too much what other people are doing—what matters is that I find a method that works for me.

I chose to take notes manually (reasons why are discussed below).

I start with a 4×6 index card, and I create a title page for the book (similar to what you would see in a bibliography with the book title, subtitle, author name, publisher, and year).

Then I write the book outline on the back of the title card, listing the sections (Part 1, 2, 3, etc.), chapters, subtitles, and additional information. This can provide context when I later review the notes. It’s also helpful in understanding how some authors structure their books.

Each Thought or Idea Gets its Own Note Card

One important rule I settled on at the beginning is limiting each card to one thought, idea, or quote. Our attention is limited and the importance of the idea should not be diminished by trying to cram as much information on each card as is humanely possible. Index cards are cheap. Ideas are valuable. Do the math.

The one idea per card rule means some cards will only have a couple of lines of text, while others may be filled front and back. That’s OK. Do what works for you.

Anatomy of a Note Card

I start with the book’s title in the upper left of the card, and I place the page number(s) in the right corner.

I skip the next line, then start with the notes. I use “quotations” to indicate anything quoted verbatim from the book, and I use a double forward slash “//” to indicate anything that is summarized or paraphrased.

Why the double forward slash? The first time I used it was out of reflex. But then I realized that’s how many programming languages allow developers to add non-executable comments to explain the subsequent block of code. Either way, it works for me. Find what works for you and you’ll be golden.

I also use enclosed brackets and ellipses […] to indicate when I have removed a section that I am quoting from the book.

Finally, I draw a line with an arrow pointing to the bottom corner of the notecard if there are additional notes on the back of the card. Again, I only put one thought or idea per card, so most cards only have content on the front. But some ideas need additional space.

Note-Taking Supplies

These are the items I use for my note-taking (all purchased from Amazon, though you can find them at most office supply stores):

- 4×6 Lined Index Cards

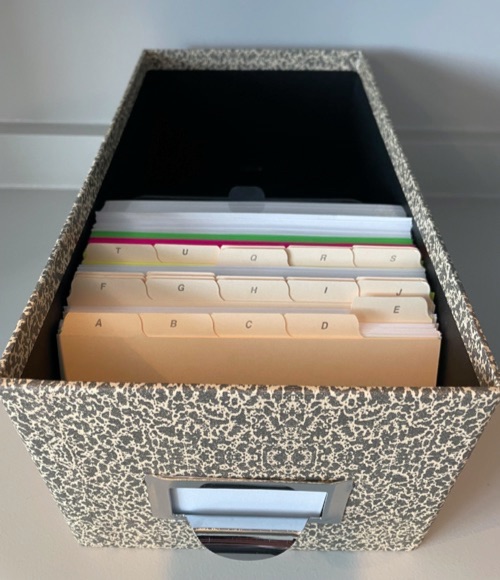

- 4×6 Index Card Storage Box (holds up to 1,000 cards)

- Alphabetized Index Card File Dividers

- Colored Index Cards (not necessary, but helpful for separating books that start with the same letter)

The total cost for this setup was less than $40 (at the time of writing).

I chose the 4×6 index cards because they hold more information than the 3×5 cards. The size is important to me because I want to limit each index card to one primary quote, thought, or idea. The larger size allows me to write on the front and back (if necessary) to capture a more complex thought or a longer summary, such as a chapter.

Note-Taking—Manual or Digital?

I chose to take notes manually. While I read a lot of ebooks on my Kindle, I prefer to read fiction in a digital format and I prefer to read non-fiction in physical form. This is because I can scream through a fiction ebook, but I find that I often flip back and forth through non-fiction books. This makes the digital format more cumbersome for non-fiction. I also like having something physical in my hands.

As for the actual note-taking itself, I find that manually writing makes me focus on being intentional about the notes I take and forces me to think deeper when summarizing passages. There may also be benefits to writing by hand including creating longer-lasting neural pathways. Likewise, I am working to ensure I have a mix of direct quotes and summarized passages. Putting notes into your own words shows you have a deeper understanding of the topic and may give you longer-lasting benefits.

Finally, I’ll have a centralized location for storing all of my notes in an organized manner.

There are downsides to manually scribing notes, of course. Typing is generally faster than writing by hand. Highlighting in Kindle and other ebook platforms is easy. And you can quickly export and download notes and highlights from your Kindle, which is a massive time-saver. To top it off, it’s easy to import those notes into Evernote, Notion, and other tools. So do this if it works for you.

Despite the benefits of digital note-taking, I am avoiding it (for now) because I think it may cause me to be lazy and less intentional with my actions. I also spend much of my day online, so I don’t want to be forced to review books on a screen when the alternative is the ability to pick up a stack of index cards and focus on only one thought or idea at a time. (How often have you signed onto your computer to do something, only to be distracted by… Look, squirrel!).

This brings me to my final point—my note-taking process intentionally includes one thought or idea per notecard. This forces me to be intentional with what I put on the card and only allows me to review a single card at a time. If the thought or idea is important enough to warrant being written down, then it is important enough for me to review it individually.

It’s difficult to give the full measure to an individual idea when staring at a screen full of great ideas. Limiting each card to one idea per card forces me to focus on the one idea in front of me—without the distraction of seeing dozens of quotes or summaries surrounding that single idea. This allows me to better internalize these ideas in their pure form.

Update: This note taking method is loosely based on Ali Abdaal’s method found in this video. I used this note taking method for several books. It works, but it’s very labor intensive. I only use it when I feel there will be a big payoff. I don’t use it for every book I read.